Chunking for Working Memory – Hallway Pedagogy

If you have a student with a learning disability or ADHD in your classroom it is likely that you have seen the suggestion for “chunking” on their accommodations list. Today I am going to talk about what chunking is and why it works for learning.

Chunking is a perfect example of a strategy that is necessary for some but helpful for all. In my own teaching practice I rarely go to any special effort to chunk lessons or assignments for individual students, because I have come to do it as part of my day to day practice. Chunking takes big learning tasks or blocks of new information and breaks them down into ‘bite sized’ chunks.

To know why chunking is necessary you have to know how working memory works. Learning science is new and evolving but, based on what we know at the moment about how the brain works, the memory is usually simplified down into two sections. Working memory and long term memory. The easiest way to think about this is like the RAM and hard drive of a computer. The working memory (or RAM) is the part of the brain that takes new information and processes it. Like your eyes see a furry blob of fur with a wagging tail and your working memory says: dog. The long term memory (or the hard drive) is where you store information to be retrieved later: I’ve seen this dog 5 times before, he belongs to my neighbor, the dog’s name is Max.

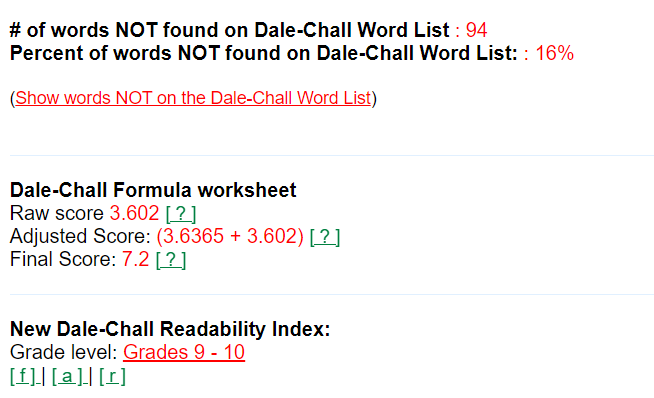

It is generally accepted that working memory is limited and long term memory is infinite. Sounds good right? Infinite memory? The problem is to get new information into long-term memory for storage it has to go through the bottle neck of working memory. How much information we can actually store in the working memory is a question that scientists continue to ask but the accepted total is between 4 and 7 distinct elements.

This is where chunking gets really important. One element is one chunk. A ‘chunk’ can be a single random number, or a string of 3 frequently used numbers (like 911) or a longer string of really familiar numbers (like your first phone number). Once a group of information has been automatized – you’ve thought about this group of information so many times your working memory recognizes it at one chunk – then it stops taking up all of the space in your brain and leaves space for new information.

To see why this is important for teachers I’m going to use an example that I see a lot as a special education teacher. Trigonometry. I usually start any intervention with a student with a joke or a funny picture because memory is very closely tied with emotion and we tend to remember the best and worst things that happen to us. Then I try to find out which parts of the process they already know how to do. Trig has lots of steps and each of these steps has to be learned and practiced individually so that they become one chunk. Otherwise you are asking a student to complete a problem that has seven steps but their working memory is filled to the brim remembering: what does 90° look like, what is a right angle, what were the names again, what does hypotenuse even mean anyway. If they are a student with ADHD they are probably also carrying around: what is that noise in the corner, how come the lights are buzzing, I wonder what we are having for dinner tonight, and I need to find the cheat codes for the next level in my video game.

Each of the steps required to solve for a missing side using trig are nicely scaffolded in the curriculum, but when you have a student who hasn’t consolidated, practiced, and chunked each of those steps you have a frustrated and overwhelmed kid really fast.

Ideally we would go back and practice and consolidate all the steps in order – that would be the best way – but also not practical in a classroom setting. Another solution is an anchor chart. I’ve made some version of a chart like this, likely 50 time. On chart paper, on scraps of paper, on white boards, sometime on the back of someone’s hand. Kids will use each chart (or sometimes pieces of one) as one ‘chunk’ and over time will stop referring to the chart as that chunk becomes consolidated and moves to long-term memory.

The important thing for you, as the teacher, to remember is that many of the chunks that you have stored away in long term memory, this is information or skills that you draw on easily because you have done them hundreds of times, will require a large percentage (or all) of a student’s working memory. For them your 1 chunk may represent 10 individual pieces of new information. Since human capacity probably maxes out at 4, you may have just asked your student to process a quantity of information that is not biologically possible – and that may only in the first step of the problem.

I say none of this is to discourage you. Human being learn new information and it gets sorted and stored into long-term memory all the time You have been through the same process your students are working through, likely in a very similar way. Your job is to know what they know and build from there – but one step at a time. This is going to be important for all your students, not just those with IEP’s.

What is a new task that you remember doing that didn’t come easily and you had to learn it piece by piece. Tell me in the comments!

Thalmann, Souza, A. S., & Oberauer, K. (2019). How Does Chunking Help Working Memory? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000578

Sousa, D. A. (2006). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Corwin Press.

Ratey, J. (2002). How the brain works: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. M.D. Vintage Books, New York.

Visually Chunking: Cut up the math worksheet / https://www.thewatsoninstitute.org/special-education-tips-visual-chunking-math/

Suggested chunks for a writing assignment: https://www.understood.org/articles/en/how-to-help-your-child-break-up-a-writing-assignment-into-chunks

Featured image: “My face, piece by piece” by angies is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Video image: “MIT+150: FAST (Festival of Art + Science + Technology): FAST LIGHT — building 54 facade, window side” by Chris Devers is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Bottle neck” by cbcastro is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Recent Comments